The Feeding Habits of Blue Whales

The largest mammal on Earth, the blue whale, has a feeding method that is just as incredible as the size of its body. These giants primarily consume krill, tiny shrimp-like creatures, through a method known as filter feeding. By taking in enormous gulps of seawater and filtering out their prey using baleen plates, blue whales can consume up to 4 tons of krill per day. But how exactly do they locate their food in the vast ocean, and what adaptations make their feeding so efficient?

In this AnimalWised article, we’ll dive deep into the feeding habits of blue whales, explore the science behind their diet, and uncover the environmental factors that influence their survival.

What is the diet of the blue whale?

Blue whales eat almost entirely krill despite being the largest animals on Earth. Their diet is simple but their feeding process is complex.

Krill are small shrimp-like crustaceans about 1-2 centimeters (0.4-0.8 inches) long. During feeding season, a blue whale can eat up to 4-8 tonnes of krill daily. This massive intake is needed to support their enormous size and energy needs.

Although krill makes up 95-98% of their diet, but blue whales occasionally eat small schooling fish, various zooplankton, and copepods when available. These alternative food sources supplement their diet but don't replace their need for krill.

A blue whale needs about 1.5 million kilocalories daily to maintain its metabolism. They feed at depths of 100-500 meters (328-1,640 feet) where krill concentrates. Most of their yearly food consumption happens during summer months when krill is abundant. During peak feeding, they lunge through krill swarms 60-70 times per day, with each mouthful containing 5,000-10,000 kg (11,023-22,046 lbs) of water and krill.

Want to impress your friends with more knowledge about Earth's biggest animal? Our other article offers additional insights that go beyond their eating habits.

What is the blue whale feeding technique?

Blue whales use a specialized feeding system that lets them process huge volumes of water to capture tiny prey. This filter-feeding approach involves several unique anatomical features working together.

Your typical blue whale has 270-395 baleen plates hanging from each side of its upper jaw. These plates consist of keratin, which is the same protein in your fingernails and hair. Each plate can grow up to 1 meter (3.3 feet) long and has a triangular shape that narrows toward the tip.

The inner edges of these plates fray into fine, hair-like bristles that create an effective sieve. These bristles interlock to form a dense mat that traps krill and other small organisms while allowing water to pass through.

When a blue whale spots a dense patch of krill, it accelerates to about 8 km/h (5 mph) and opens its mouth to approximately 90 degrees. As water rushes in, the whale's pleated throat grooves expand dramatically. These 60-90 accordion-like folds run from the chin to the navel and allow the throat to stretch to four times its resting size.

During a single gulp, a blue whale can take in up to 70,000 liters (18,492 gallons) of water, which equals the volume of a school bus. This creates enormous drag, slowing the whale from its initial speed to almost a complete stop in just a few seconds.

The whale's tongue, which can weigh as much as an elephant, retracts to make room for this massive water intake. The process requires significant energy, about 770 kilocalories per lunge.

After capturing a mouthful of krill-laden water, the whale closes its mouth and uses its tongue and muscles to push the water outward. The water passes through the baleen plates while the krill gets trapped against the bristled mat.

The pressure created by the whale's muscular tongue forces water between the baleen plates and out through the sides of the mouth. This process takes about 60 seconds. Once most water is expelled, the whale uses its tongue to collect the trapped krill from the baleen surface and swallows them whole.

This filtering system is quite effective, a blue whale can process about 2,000 krill in a single gulp. During peak feeding season, blues perform this gulping action up to 70 times per day, allowing them to consume millions of krill within hours.

What do blue whale calves eat?

Blue whale calves feed exclusively on their mother's milk for the first 6-8 months of life. This milk is extremely rich in fat (about 30-50% fat content) compared to human milk (around 4%), allowing calves to grow rapidly.

A blue whale calf drinks about 380-570 liters (100-150 gallons) of milk per day. This high-calorie diet helps them gain weight at an impressive rate, approximately 90 kg (200 lbs) per day during their first year.

The mother produces this milk through mammary glands located on her underside. Unlike many mammals, blue whale calves must actively swim alongside their mother and nudge her to stimulate milk release. The mother then squirts the milk directly into the calf's mouth, as the saltwater environment would quickly dilute any milk that simply flowed out.

After the nursing period, blue whale calves gradually transition to eating krill. The mother teaches the calf hunting techniques during this weaning phase. By the time they're fully weaned at 7-8 months old, calves have typically grown to about 15 meters (49 feet) in length, which is roughly half the size of an adult blue whale.

This intensive nursing period represents a massive energy investment for the mother, who might lose up to 25% of her body weight while producing milk for her calf.

Fascinated by blue whales? Explore the entire family of marine mammals they belong to in our other article.

What is the feeding pattern of the blue whale?

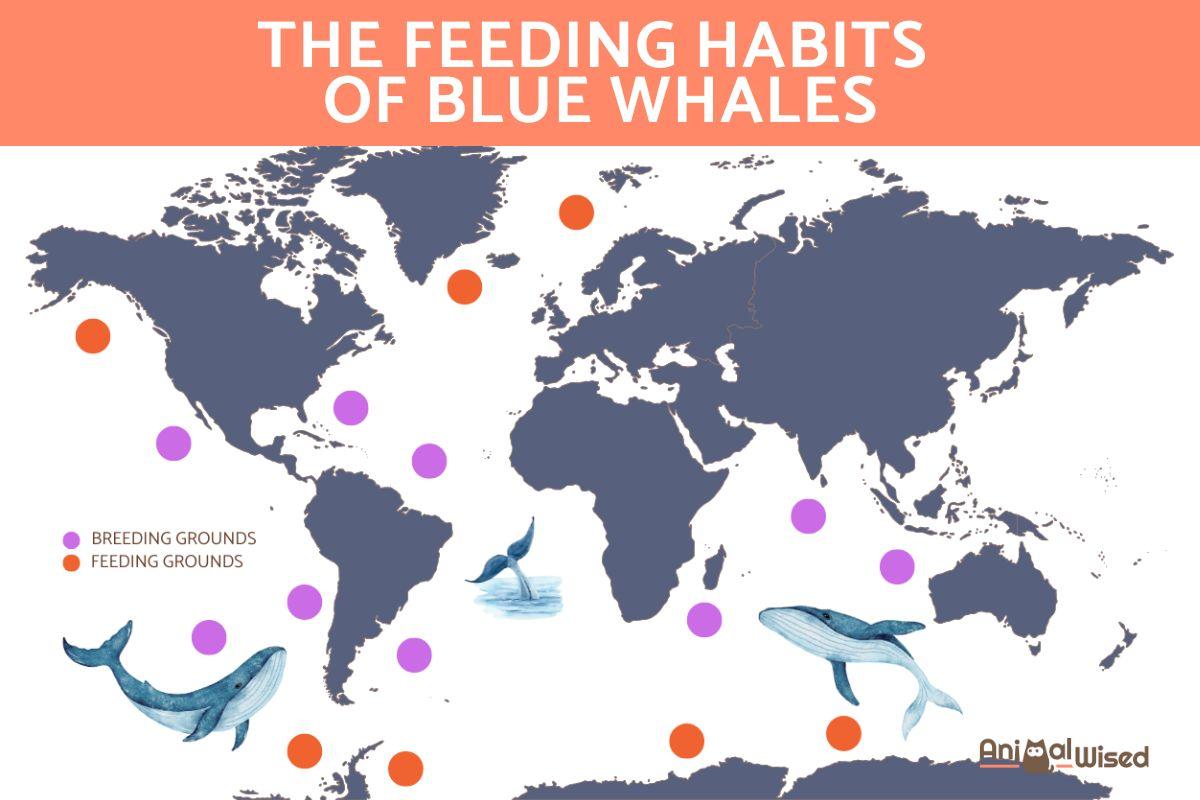

Due to their requirement to locate an abundance of krill, blue whales migrate along predictable patterns. They move in distinct ways throughout the year as they transition between the feeding and breeding seasons.

A single blue whale population might travel 5,000-8,000 km (3,100-5,000 miles) between summer feeding grounds and winter breeding areas. They travel these great distances with amazing accuracy, returning year after year to the same feeding grounds with historically high krill concentrations.

As summer arrives, blue whales journey to polar and subpolar seas, drawn by the feast of krill. These waters, rich in nutrients and chilled by the polar climate, erupt with plankton, providing a vital food source for the massive krill swarms.

- Northern Hemisphere populations: feed primarily in the Gulf of Alaska, Gulf of California, and waters near Greenland.

- Southern Hemisphere populations: feed in waters surrounding Antarctica.

As winter approaches, blue whales travel to warmer tropical or subtropical waters to breed and give birth. These areas include waters near Costa Rica, Mexico, and parts of the Indian Ocean. During this migration to breeding grounds, they fast or eat minimal amounts, living off fat reserves built up during summer feeding.

Blue whale feeding success is closely linked to ocean currents. Specifically, upwelling zones, where nutrient-rich, cold water rises from the depths, create prime breeding grounds for krill. This, in turn, draws blue whales to these areas.

Moreover, sea temperature is a significant factor that determines the movement of blue whales and the distribution of krill. Krill thrive in a limited temperature range of 0–3°C (32–37°F), and they can move due to even small temperature changes.

Consequently, blue whales must adapt, often deviating from established migration paths to pursue these shifting food sources.

How does environmental change affect blue whales?

Climate change is disrupting blue whale feeding patterns. Rising ocean temperatures are already altering krill distribution, driving these vital food sources towards cooler polar regions and diminishing their abundance in traditional feeding grounds. This is particularly evident in the Southern Ocean, where krill populations have plummeted by up to 80% in some areas since the 1970s.

Consequently, blue whales are forced to expend significantly more energy searching for food over greater distances. Adding to this challenge, the feeding season is shrinking as warming occurs earlier each year, leaving whales less time to accumulate the crucial fat reserves they need for migration and reproduction.

Several factors contribute to this decline, let us take a closer look at some of them:

- Ocean acidification: as the ocean absorbs more carbon dioxide, its pH level drops, threatening krill's exoskeleton development and reproduction. This increased acidity leads to higher mortality rates among young krill, potentially causing population collapses in critical feeding areas.

- Commercial shipping routes: the overlap between these routes and blue whale feeding grounds creates a significant risk of vessel strikes. Collisions with large ships are almost always fatal for blue whales.

- Underwater noise pollution: noise from ships, seismic surveys, and military sonar disrupts blue whale feeding behaviors. Studies demonstrate that these noise levels can force whales to abandon rich feeding areas and interfere with their communication systems, essential for locating krill swarms.

- Microplastic contamination: an emerging threat, microplastics concentrate in krill, which are then consumed by blue whales. This introduces toxins that can negatively impact the whales' health and reproductive success.

- Overfishing of krill: the harvesting of krill for aquaculture feed, pharmaceuticals, and nutritional supplements further reduces food availability. Even with regulations in place, annual commercial krill harvests remove thousands of tonnes from blue whale feeding grounds.

Climate change and human activities impact blue whale feeding patterns, but how severely is this affecting their overall survival? Find out in our related article.

If you want to read similar articles to The Feeding Habits of Blue Whales, we recommend you visit our Healthy diets category.